|

Case Study 3: Growing an Application from Collaboration to

Management Support—The Example of Cuparla |

|

Gerhard Schwabe |

|

|

|

Analysis and Design |

|

Just like in other towns, members of the

Stuttgart City Council have a large workload: In addition to their primary

profession (e.g., as an engineer at Daimler Benz) they devote more than 40

hours a week to local politics. This extra work has to be done under fairly

unfavorable conditions. Only council sessions and party meetings take place

in the city hall; the deputies of the local council do not have an office in

the city hall to prepare or coordinate their work. This means, for example,

that they have to read and file all official documents at home. In a city

with more than 500,000 inhabitants they receive a very large number of

documents. Furthermore, council members feel that they could be better

informed by the administration and better use could be made of their time.

Therefore Hohenheim University and partners* launched the Cuparla project to

improve the information access and collaboration of council members.

A detailed analysis of their work revealed the following characteristics

of council work: |

When designing computer support we initially had to decide on the basic

orientation of our software. We soon abandoned a workflow model as there

are merely a few steps and there is little order in the collaboration

of local politicians. Imposing a new structure into this situation would

have been too restrictive for the council members. We then turned to

pure document-orientation, imposing no structure at all on the council

members’ work. We created a single large database with all the documents

any member of the city council ever needs. However, working with this

database turned out to be too complex for the council members. In addition,

they need to control the access to certain documents at all stages of

the decision-making process. For example, a party may not want to reveal

a proposal to other parties before it has officially been brought up

in the city council. Controlling access to each document individually

and changing the access control list was not feasible.

Therefore, the working context was chosen as a basis of our design.

Each working context of a council member can be symbolized by a “room.”

A private office corresponds to the council member working at home;

there is a party room, where he collaborates with his party colleagues,

and a committee room symbolizes the place for committee meetings. In

addition, there is a room for working groups, a private post office,

and a library for filed information. All rooms hence have an electronic

equivalent in the Cuparla software. When a council member opens the

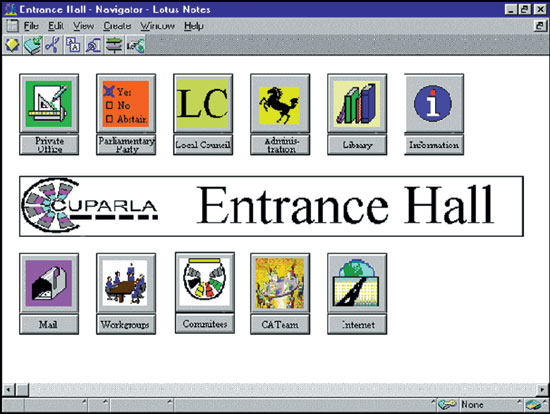

Cuparla software, he sees all the rooms from the entrance hall (Figure

1).

Figure 1: Entrance hall

The council member creates a document in one room (e.g., his private

office) and then shares it with other council members in other rooms.

If he moves a document into the room of his party, he shares it with

his party colleagues; if he hands it on to the administration, he shares

it with the mayors, administration officials, and all council members.

The interface of the electronic rooms resembles the setup of the original

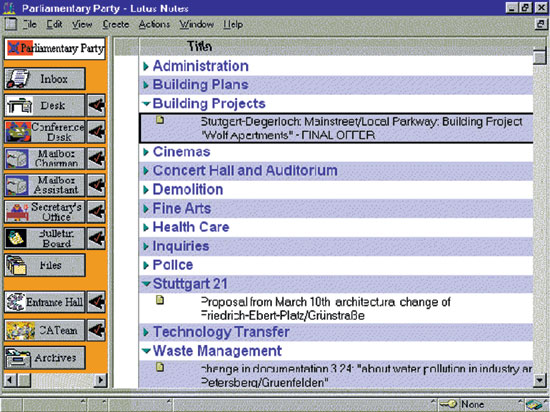

rooms. Figure 2 shows the example of the room for a parliamentary party.

On the left hand side of the screen there are document locations, whereas,

on the right hand side, the documents of the selected location are presented.

Documents that are currently being worked on are displayed on the “desk.”

These documents have the connotation that they need to be worked on

without an additional outside trigger. If a document is in the files,

it belongs to a topic that is still on the political agenda. However,

a trigger is necessary to move it off of the shelf. If a topic is not

on the political agenda any more, all documents belonging to it are

moved to the archive. |

|

|

|

Figure 2 Parliamentary party room |

|

The other locations support the collaboration within the party. The

conference desk contains all documents for the next (weekly) party meeting.

Any council member of the party can put documents there. When a council

member prepares for the meeting, he or she merely has to check the conference

desk for relevant information. The mailbox for the chairman contains

all documents that the chairman needs to decide on. In contrast to his

e-mail account all members have access to the mailbox. Double work is

avoided as every council member is aware of the chairman’s agenda. The

mailbox of the assistant contains tasks for the party assistants; the

mailbox for the secretary, assignments for the secretary (e.g., a draft

for a letter). The inbox contains documents that have been moved from

other rooms into this room.

Thus, in the electronic room all locations correspond to the current

manual situation. Council members do not have to relearn their work.

Instead, they collaborate in the shared environment they are accustomed

to with shared expectations about the other peoples’ behavior. Feedback

from the pilot users indicates that this approach is appropriate.

Some specific design features make the software easy to use. The software

on purpose does not have a fancy three dimensional interface that has

the same look as a real room. Buttons (in the entrance hall) and lists

(in the rooms) are much easier to use and do not distract the user from

the essential parts. Each location (e.g., the desk) has a little arrow.

If a user clicks on this arrow, a document is moved to the location.

This operation is much easier for a beginner than proceeding by “drag

and drop.”

Furthermore, software design is not restricted to building an electronic

equivalent of a manual situation. If one wants to truly benefit from

the opportunities of electronic collaboration support systems, one has

to include new tools that are not possible in the manual setting. For

example, additional cross-location and room search features are needed

to make it easy for the council member to retrieve information. The

challenge of interface design is to give the user a starting point that

is close to the situation he is used to. A next step is to provide the

user with options to improve and adjust his working behavior to the

opportunities offered by the use of a computer. |

|

Organizational Implementation |

|

Building the

appropriate software is only one success factor for a groupware project.

Organizational implementation typically is at least as difficult. Groupware

often has a free rider problem: All want to gain the benefit and nobody wants

to do the work. Furthermore, many features are only beneficial if all

participate actively. For example, if a significant part of a council faction

insists on using paper documents for their work, providing and sharing

electronic documents actually means additional work for the others. This can

easily lead to the situation that groupware usage never really gets started.

To “bootstrap” usage we started with the (socially) simple activities and

ended with the (socially) complex activities (Figure 3). |

|

Figure 3: Steps of groupware implementation |

|

In the first step we provided the basic council information in digital

form. The city council has the power to demand this initial organizational

learning process from the administration. Once there is sufficient information

the individual council member can already benefit from the system without

relying on the usage of his fellow councillors. The usage conventions

are therefore socially simple. As better information is a competitive

advantage for a council member, there was an incentive for the individual

effort required to learn the system. Communication support (e-mail,

fax) is a more complex process, because its success depends on reliable

usage patterns by all communication partners. The usage patterns are

straightforward and easy to learn. We therefore implemented them in

a second phase. Coordination activities (sharing to-do lists, sharing

calendars) and cooperation activities (sharing documents and room locations,

electronic meetings) depend on the observance of socially complex usage

conventions by all group members. For example, the council member had

to learn that her activities had effects on the documents and containers

of all others and that “surprises” typically resulted from ill-coordinated

activities of several group members. The council has to go through an

intensive organizational learning process to benefit from the features.

For example, the party’s business processes had to be reorganized.

We offered collaboration and coordination support in the same phase

to the council members. Their appropriation depended on the party’s

culture: A hierarchically organized party preferred to use the coordination

features and requested to turn off many collaborative features. In another

party most councilors had equal rights. This party preferred the collaborative

features. |

|

Economic Benefits |

|

The ultimate success

of any IS project is not only determined by the quality of the developed

technology but also by its economic benefits. Thus, the economic benefit of

Cuparla was evaluated in the first quarter of 1998 after about four months of

use by the whole city council (pilot users had been using the system for more

than a year). Evaluating the economic benefits of innovative software is

notoriously difficult. Reasons for that include |

The evaluation of Cuparla was therefore not based on purely monetary

terms; rather evaluation results were aggregated on five sets of criteria

(cost, time, quality, flexibility, and human situation) and four levels

of aggregation (individual,group, process, organization) resulting in

a 4 X 5 matrix (Figure 4). |

|

Figure 4: Aggregated evaluation of Cuparla (March 1998) |

|

The trick is to attribute

the effects only to the lowest possible level, (e.g., if one can attribute

the cost of an individual PC to an individual council member, it counts

only there and not on the group level). On the other hand, a server

probably can only be attributed to the group of all council members

and so on. We will now briefly go through the major effects:

Costs Both on the individual

and the group level costs have gone up significantly (notebooks, ISDN,

printer, server, etc.). There is a potential for cost savings if the

council members forgo the delivery of paper copies of the documents.

There have been some additional costs on the process level, but not

as much as on the two levels below. There may have been direct cost

savings by the provision of electronic documents in the council related

business processes, but we were not able to identify them. As the administration

was reluctant to really reorganize its internal business processes,

many potential cost savings could not be realized. As all costs could

be attributed to the levels business process, group or individual, we

noted a cost neutrality for the level “organization” (the costs for

provisionally wiring the city hall were negligible).

Time During the pilot phase,

the system did not save time for the councilors; to the contrary, the

individual councilors had to work longer in order to learn how to use

the Cuparla system. However, the councilors also indicated that they

used their time more productively, (i.e., the overtime was well invested).

Thus, we decided to summarize the effects on the individual level as

“neutral.” Cuparla had also not yet led to faster or more efficient

decisions in the council or its subgroups. Therefore the effects are

graded “unchanged.” The council members see potential here, but the

speed of decisions is not only a matter of work efficiency but also

has a political dimension and politics does not change that fast. Some

business processes were rated as being faster, particularly the processes

at the interface between council and administration (e.g., the process

of writing the meeting minutes). There was no effect on the organization

as a whole; (i.e., the city of Stuttgart was not faster at reacting

to external challenges and opportunities).

Quality The council members

reported a remarkable improvement of quality of their work. The council

members feel that the quality of their decisions has been improved by

the much better access to information. The work of the parties has benefited

from the e-mail and the collaboration features of Cuparla as well as

the computer support of strategic party meetings. As the interface between

different sub-processes of council work has fewer media changes and

the (partially erroneous) duplication of information has been reduced,

the council members and members of the administration also reported

an improved quality of their business processes. The creation of an

organization-wide database of council-related information even contributed

to a somewhat better work in the whole administration.

Flexibility Improved individual

flexibility was the most important benefit of Cuparla. This holds true

for spatial, temporal, and interpersonal flexibility. People can work

and access other people any place and any time they want. On the group

level Cuparla has enhanced the flexibility within parties as it has

become easier to coordinate the actions of the council members. There

have not been any significant changes to the flexibility on the process

or organizational levels.

Human situation Cuparla has made council membership more attractive because it

has become easier to reconcile one’s primary job, council work, and

private life. Furthermore Cuparla is regarded as an opportunity for

the council member’s individual development. There were no significant

changes to the human situation on the group, process, or organizational

levels. |

|

Towards a Management Support System |

|

As mentioned above, these effects were

measured after a relatively short period of usage. In 2002, the author

returned to Stuttgart and investigated how Cuparla had been adopted five

years after the initial implementation: Cuparla has become an indispensable

part of council work. Almost all council members used Cuparla frequently.

Interestingly, some original features of Cuparla were only adopted years

after the original software implementation; most important, the rooms for

subgroup collaboration.

Although the change slowed down after the initial organizational implementation

phase, the system continued to grow due to user demand and organizational

change:

Still, the open motions list was a huge success and marked the move

of Cuparla from a pure Information and Cooperation Support System towards

a Management Support System. In the meantime Andreas Majer, the local

project manager of Cuparla, had been promoted to head the IT department.

He decided to further develop the concepts of Cuparla into a Management

Support System (MSS), mainly for two reasons:

Andreas Majer uses an example to describe his vision of an MSS: “Imagine

a city councilor wants to analyze the success of a program providing

social workers for difficult schools. Parts of the answers he will find

in the official council documents dealing with the local schools. Statistical

data on the schools and their neighborhoods will be provided by the

statistical information system Communis and the funding for each school

can be extracted from the ERP system. The existing plans for the development

of the schools are explained in the yearly planning document and the

geographical situation of each school can be referenced on the digital

map in the Geographic Information System. Currently, each piece of information

has to be retrieved from another information system. In a Management

Support System one application should suffice to provide all relevant

information and the information should be linked.”

However, with the growth of the system, Cuparla reached its limits:

Since its roots are a collaboration system, its interface and architecture

are not sufficiently prepared for information and application integration.

Therefore Stuttgart decided to start redesigning Cuparla in late 2002.

The future interface will include some cockpit-functionality, allowing

each council member to monitor significant performance indicators. Furthermore,

a comprehensive search functionality will support integrated queries

of several information sources. The major architectural challenge will

be data integration: In order to display the relationships between data

items, a data warehouse needs to be constructed. Finally, there will

be several interfaces, because council members increasingly rely on

PDAs and mobile phones for information access. As user needs and organizational

challenges change, Cuparla will continue to grow and adapt. |

|

Case Study Questions |

|

|

Additional Reading |

|

Schwabe, G. and

Krcmar, H. “Piloting a Sociotechnical Innovation.” Appears in the Proceedings

of the 8th European Conference on Information Systems ECIS 2000,

Wirtschaftsuniversität Vienna, Vienna 2000, p. 132–139. |